Blocking a Stress-response Protein Found to Treat PH in Animal Model

People with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) have higher than usual levels of a protein produced in cells in response to shock or stress — called heat shock protein 90 or HSP90 — and diminishing those levels helped to prevent pulmonary hypertension from progressing in a rat model of the disease, researchers reported.

Their study, “Inhibition of heat shock protein 90 improves pulmonary arteriole remodeling in pulmonary arterial hypertension,” was published in the journal Oncotarget.

HSP90 is also known as a molecular chaperone, because it works to help proteins fold properly or refold after exposure to stress, among other tasks. As such, HSP90 is involved in many physiological and pathological processes. It has been studied primarily in cancer because of its role in cell division, and because it regulates the maturation of several signaling proteins in cells — including kinases (undirected movement), steroid hormone receptors, and key cancer proteins.

Recently, a chemical inhibitor of HSP90 — 17-allylamino-17-demethoxygeldamycin (17-AAG) — was shown to reduce inflammation and suppress the migration and rapid growth of vascular smooth muscle cells in atherosclerosis, which in turn reduced the buildup of the damaging plaque inside arteries.

In this study, researchers investigated the expression levels of HSP90 in PAH patients, and evaluated how a HSP90 inhibitor, 17-AAG, affected pulmonary arteriole remodeling and the rapid growth of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs).

Researchers analyzed 27 plasma samples from coronary heart disease patients with PAH, 39 coronary disease patients without PAH, and 23 healthy controls. They found that HSP90 levels were high in samples from the PAH patients.

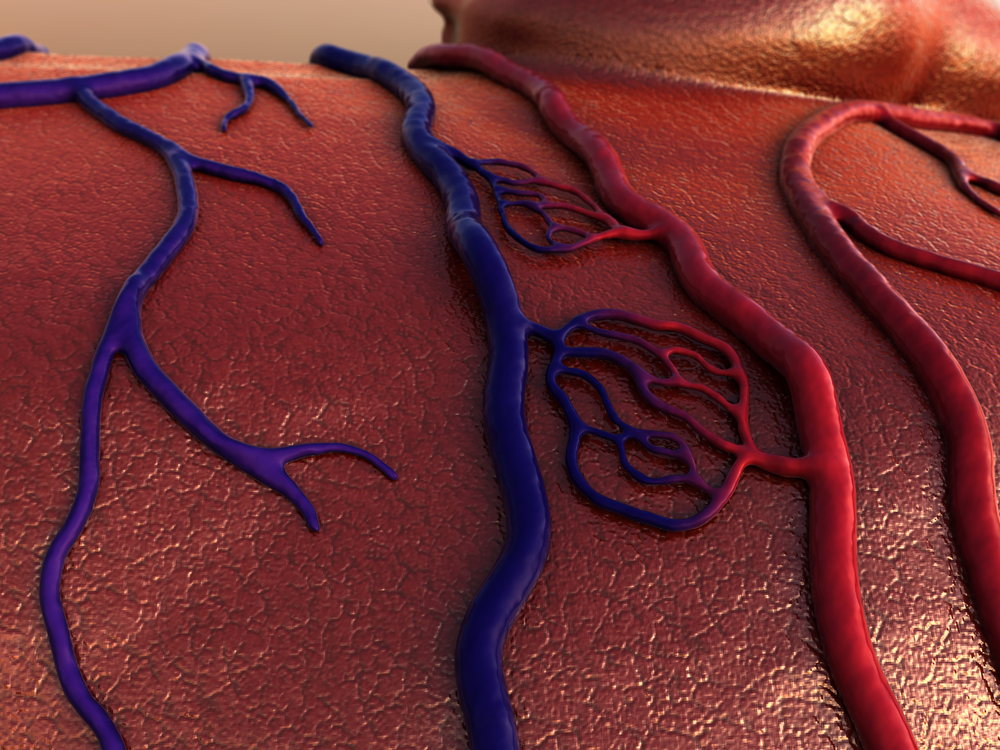

They also found increased levels in the membrane walls of pulmonary arterioles, or small branches of lung arteries, in these patients. In fact, the levels of HSP90 correlated well with average pulmonary arterial pressure and C-reactive protein (a key protein whose levels increase in response to inflammation).

To understand on a more physiological level how inhibiting HSP90 impacts PAH progression, researchers next took rats altered to develop pulmonary hypertension (PH), known as the monocrotaline-induced rat model, and treated them with the HSP90 inhibitor, 17-AAG.

Researchers found that 17-AAG alleviated PH progression in the animals, indicated by a lower pulmonary arterial pressure and lack of right ventricular hypertrophy (which occurs when the heart’s right ventricular wall thickens due to chronic pressure overload). The treatment also improved pulmonary arteriole remodeling by reducing the thickness of the ventricular wall and wall area.

Additionally, researchers discovered that 17-AAG suppressed platelet-derived growth factor-stimulated rapid growth, and the migration of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells by blocking the cells’ cycle of division.

“HSP90 inhibitor 17-AAG could improve pulmonary arteriole remodeling via inhibiting the excessive proliferation of PASMCs, and inhibition of HSP90 may represent a therapeutic avenue for the treatment of PAH,” they concluded.