Sister’s PH Diagnosis Followed Years of ‘Allergies or Asthma’ Talk, Debbie Drell of NORD Says

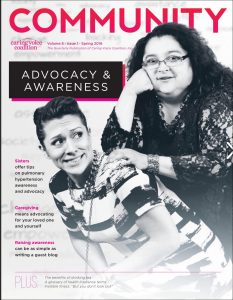

Debbie Drell, left, and her sister Alex at a NORD award ceremony in May 2017. (Photo courtesy Debbie Drell)

Debbie Drell, director of membership at the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD), knows all too well about rare diseases.

Her older sister, Alex Flipse, was diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension (PH) in September 1998 after enduring five years of worsening symptoms. Drell was told she also had a rare form of PH in the mid-2000s — but that diagnosis turned out to be false.

Not surprisingly, she became an expert on the disease, which affects about 30,000 Americans at any given time.

Drell spent 13 years as senior director of patient and caregiver services at the Pulmonary Hypertension Association (PHA).

During that time, she helped grow the PHA’s network of support groups from 80 to nearly 300. She also developed new services tailored for patients of all ages, and played a key role in coordinating the largest gathering of PH patients in history. Today, the PHA — based in Silver Spring, Maryland — has evolved into a community of thousands of PH patients, caregivers, family members and medical professionals. Its Facebook page notes over 23,000 followers.

In early 2016, both sisters were featured in a cover story for Community, the quarterly publication of Caring Voice Coalition, a nonprofit group that provides financial support to people with rare diseases.

“When Alex was diagnosed with PH, she was 28 years old. She had already fainted once. Then, many years later, after her third baby, all the symptoms came,” Drell said at a recent interview with Pulmonary Hypertension News during NORD’s Rare Diseases & Orphan Products Breakthrough Summit in Washington, D.C.

“One doctor after another told her she had allergies or asthma,” Drell added. “They told her to lose weight and exercise more. She had difficulty breathing and even got a prescription for Prozac. She would vomit after eating because her body couldn’t take the energy of digesting food.”

Drell visited her sister at every summer break while she was at college, and remembers watching her decline.

“One summer, Alex wouldn’t get off the couch,” she said. “I told her, ‘Get off the couch, what’s wrong with you?’ Now I feel so bad thinking about it. I remember her eating a meal and then throwing it out. I knew it wasn’t bulimia.”

A serious misdiagnosis

Drell was with her sister at home in the rural town of Cuero, Texas, the day she had her fourth grand mal seizure.

“Her heart was so overworked. She was 98 pounds and 5-foot-1,” Drell said. “One day she went to take out the trash. When she came back in, her whole body started convulsing. Her husband was there; he was scared, too.”

That incident led to a scramble to find out what was wrong with Flipse. After seeing almost a dozen doctors, one finally diagnosed her disease: pulmonary hypertension. He sent Flipse to a specialist in Houston — a four-hour drive from Cuero — who told her that if the referring doctor hadn’t discovered her PH, she would have died within six months.

In fact, said Drell, 50 percent of people with PH will die within two years of diagnosis if left untreated.

“I got diagnosed with pulmonary arterial hypertension in 2004, but it was a false diagnosis,” she said. “I started getting symptoms. When I climbed up stairs, I was breathless and my heart was racing. I went to a cardiologist in Silver Spring who did an echocardiogram and told me I had PAH. The fact that the words came out of her mouth and that I put so much value in what physicians say made me doubt myself.”

It was only after getting a second opinion at the now PHA-accredited Johns Hopkins Pulmonary Hypertension Clinic in Baltimore that Drell learned she did not, in fact, have PH.

“Because of construction in my condo, I had an allergic reaction to exposure to the poor air quality, and somehow they manifested themselves as symptoms,” she said. “My sister has PH, so naturally you would think maybe it’s genetic. We now know that it’s not, but at the time, we had not been tested.”

Only 11 percent of PH cases are hereditary, according to the World Health Organization, which has established five distinct classifications of PH. Across these types are more than 30 different, specific ways people can develop the disease. Roughly 68 percent of patients in developed countries have PH due to left heart disease; another 9 percent have it due to chronic lung disease, the PHA says.

Drell, 40 and a native of San Diego, came to Washington, D.C., in 1999 to work on women’s health issues, and has remained in the D.C. metro area since. Her older sister, now a 47-year-old divorced grandmother, doesn’t have a car. She struggles to pay for health insurance, medicines and rent. In addition, the therapies she’s taking for PH have caused her to gain considerable weight, further complicating her health issues.

“She’s too sick to work, and she gets minimal money from Social Security,” said Drell, noting that PH patients are often financially strapped because of their disability.

NORD’s partnership with PHA

Drell left the PHA in April to become membership director at the Washington office of NORD, which is headquartered in Danbury, Connecticut.

“Debbie brings a wealth of personal and professional advocacy experience to NORD, including grassroots engagement and building strong rare disease patient communities,” Pamela K. Gavin, NORD chief operating officer, said in a press release.

At NORD, Drell coordinates the participation of 260 patient organizations — including the PHA — and nearly 700 executive directors, founders, chief scientific officers, and others. She says patients with PH benefit from this partnership in numerous ways.

While at PHA, Drell worked closely with Michael Patrick Gray, the organization’s senior director of medical services. Speaking last month at NORD’s rare disease summit, Gray stressed the importance of promoting earlier diagnosis of rare diseases.

“We’re lucky enough to have 14 targeted therapeutics, but the time to diagnosis has not changed over the years,” Gray said, adding that patients need better access to diagnostics.

“Unless you’re sitting on half a billion dollars, we can’t go to every healthcare provider and discuss our disease. Consider this group of people: all have shortness of breath, and some people have COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease], and some have asthma. We have to figure out how to talk to all these people,” Gray said.

“We don’t have a good biomarker or genetic test for PH, but we do have a screening tool. So if you have a patient with unexplained shortness of breath, order an echocardiogram,” he advised. “That’s a primary action step.”