BMPR2 Signaling Pathway a Goldmine for New Drug Targets to Treat Pulmonary Hypertension

Written by |

Pulmonary hypertension can result from a number of causes: liver diseases, lung diseases, rheumatic disorders, low oxygen, poor health behaviors and can also be inherited. More than 80% of cases resulting from a genetic predisposition to the disease are due to a mutation in the bone morphogenic protein receptor 2 gene (BMPR2). Scientists have spent the past decade working to understand the molecular mechanisms leading from BMPR2 signaling in hopes of developing treatments that specifically treat the cause of disease rather than only the symptoms. Three general approaches to tackling irregular BMP signaling have been explored: fix either upstream or downstream signaling, or both. Other approaches are also in their infancy, and any is likely to lead to new therapies.

Pulmonary hypertension can result from a number of causes: liver diseases, lung diseases, rheumatic disorders, low oxygen, poor health behaviors and can also be inherited. More than 80% of cases resulting from a genetic predisposition to the disease are due to a mutation in the bone morphogenic protein receptor 2 gene (BMPR2). Scientists have spent the past decade working to understand the molecular mechanisms leading from BMPR2 signaling in hopes of developing treatments that specifically treat the cause of disease rather than only the symptoms. Three general approaches to tackling irregular BMP signaling have been explored: fix either upstream or downstream signaling, or both. Other approaches are also in their infancy, and any is likely to lead to new therapies.

To address upstream signaling, scientists generally ask the question: can BMPR2 expression be altered to affect the way signals are initiated? To answer this question, researchers have focused on the two types of BMPR2 mutations that occur in patients with heritable pulmonary hypertension. The first class causes premature termination codons and a shortened receptor that activates nonsense-mediated decay pathways (NMD+), and the second class does not (NMD-). After studying families who are either NMD+ or NMD-, scientists have made hypotheses concerning effective treatments for either class. NMD+ patients may benefit from drugs that increase BMPR2 expression, and NMD- patients may benefit from drugs that promote synthesis of the entire BMP2 receptor. Bioinformatics tools such as the Connectivity Map database can be used to screen for such drugs.

[adrotate group=”4″]

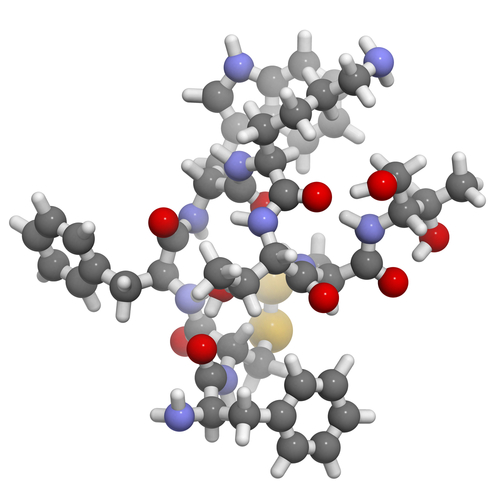

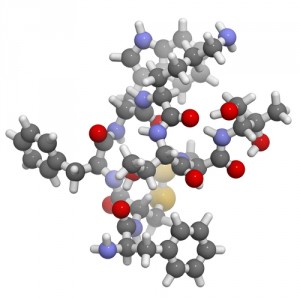

On the other side of the receptor is downstream signaling, which also comes in two forms: signals that act through proteins known as SMADs and signals that affect the organization of a cell’s “skeleton,” otherwise known as the cytoskeleton. The majority of patient mutations affect cytoskeletal arrangement rather than SMAD signaling, so most researchers focus on targeting therapeutics to defects in the cytoskeleton. The pharmaceutical company Novartis is investigating small molecule inhibitors in BMPR2 mutant mice to correct vascular leakage resulting from cytoskeletal alterations. In addition to these inhibitors, angiotensin-converting enzyme(ACE)-boosting drugs are also attractive due to their effects to increase cell-cell adhesion. Recombinant forms of ACE2 have not been developed to treat pulmonary hypertension, but a current clinical trial sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline is investigating a recombinant form of ACE2 to treat acute lung injury, making their drug the closest to being ready for human trials with pulmonary hypertension.

Of note is new work that goes beyond pure upstream/downstream BMP signaling. Some scientists have taken to heart the fact that pulmonary hypertension subtypes are more prevalent among females than males. As a result, some scientists have been exploring crosstalk between estrogen and BMP and have generated data supporting the hypothesis that altered BMP signaling modifies estrogenic activity. However, most studies are in their infancy, as the relationship between BMP signaling and estrogenic activity is complex.

[adrotate group=”3″]

No one approach to treating heritable pulmonary hypertension is likely to be “the best.” This reality is underscored by the fact that variability among patients results in a variety of signaling mechanisms that may be altered in disease. It is important that scientists continue along all avenues in order to develop drugs to be used in clinical trials, and some avenues have already led to potential drug candidates. The outlook of the scientific community is positive, with predictions that new, effective therapies for pulmonary hypertension will be available in the next few years.

The information contained herein sources from an article published in Drug Discovery Today by researchers at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, TN.