Lung Fibrosis High Risk in Elderly Unveiled by University of Pittsburgh Team

Misshapen and bloated mitochondria in the lungs may be the reason why so many elderly develop idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), according to a study conducted at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. The research, which will be featured on the cover of the February issue of the Journal of Clinical Investigation, has for the first time unveiled the reasons for the increase of the risk of developing the life-threatening lung disease associated with age.

Even though it was already known that age is a risk factor for the development of IPF, a progressive lung condition that causes fibrosis or scarring of the tissue, and consequently difficulties in breathing and even death within three to five years without a lung transplant, the reason for it was unknown. In fact, the cause of the disease is yet to be discovered, which is why it is called “idiopathic” pulmonary fibrosis.

“Other chronic and progressive diseases we see with aging, such as Parkinson’s disease, have been recently associated with mitochondrial abnormalities, so we wondered if that was occurring in IPF,” explained Ana L. Mora, M.D., the senior investigator in the study “PINK1 deficiency impairs mitochondrial homeostasis and promotes lung fibrosis,” which is currently available online.

“It was a simple question, but it hadn’t been asked before, so we examined lung cells from patients with advanced IPF and healthy people. We were so surprised to see dramatic differences in the number, shape and function of the mitochondria,” added Mora, who also serves as assistant professor in the Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine and as a member of the Heart, Lung, Blood and Vascular Medicine Institute (VMI) at Pitt.

[adrotate group=”3″]

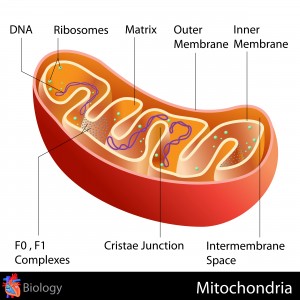

In the study, the scientists characterized the oddities of mitochondria, which are responsible for the energy in the cells, and analyzed the levels of the PTEN-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1) enzyme, which is in charge of the function and morphology of mitochondria. They concluded that mitochondria impairment was related to a reduction in PINK1 expression, and mice lacking PINK1 had dysfunctional, misshapen mitochondria in lung cells, making them more likely to suffer lung fibrosis.

“We found also that low PINK1 is associated with increasing age and cellular stress,” the researcher said. “This might help explain why older people are at greater risk for developing IPF, and it could mean developing drugs that can boost PINK1 levels or improve mitochondrial function will help treat IPF.”

“These findings are remarkable as they identify a similar disease pathway to that seen in other age related brain diseases,” added the professor and chief, Division of Pulmonary, Allergy and Critical Care Medicine, and VMI director, Mark Gladwin, M.D., who did not participate in the study. “This is the first study to find that the mitochondria themselves, the energy factories of our cells, are altered with lung fibrosis.”

The research team will now continue its work, as they hope to be able to find biomarkers to determine the disease and improve early stage diagnosis, as well as to be able to identify different factors that raise the susceptibility of developing IPF.

The studies, which were supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Vascular Medicine Institute at the University of Pittsburgh, the Institute for Transfusion Medicine, and the Hemophilia Center of Western Pennsylvania, were also conducted by Marta Bueno, Ph.D., Yen-Chun Lai, Ph.D, Judith Brands, Ph.D., Claudette St. Croix, PhD., Christelle Kamga, Ph.D., Catherine Corey, John Sembrat, Janet S. Lee, M.D., Steve R. Duncan, M.D., Mauricio Rojas, M.D., Sruti Shiva, Ph.D., and Charleen T. Chu, M.D., Ph.D., from the University of Pittsburgh, as well as Yair Romero, of Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Ciudad Universitaria, Mexico City, Mexico, and Jose D. Herazo-Maya, M.D., of Yale University.