Specific Stem Cells May Contribute to Pulmonary Hypertension, Vanderbilt Study Finds

Written by |

Stem cells known as mesenchymal progenitor cells (MPCs) may contribute to the blood vessel anomalies causing pulmonary hypertension (PH), says a new study, “Disruption of lineage specification in adult pulmonary mesenchymal progenitor cells promotes microvascular dysfunction,” that appeared in the Journal of Clinical Investigation.

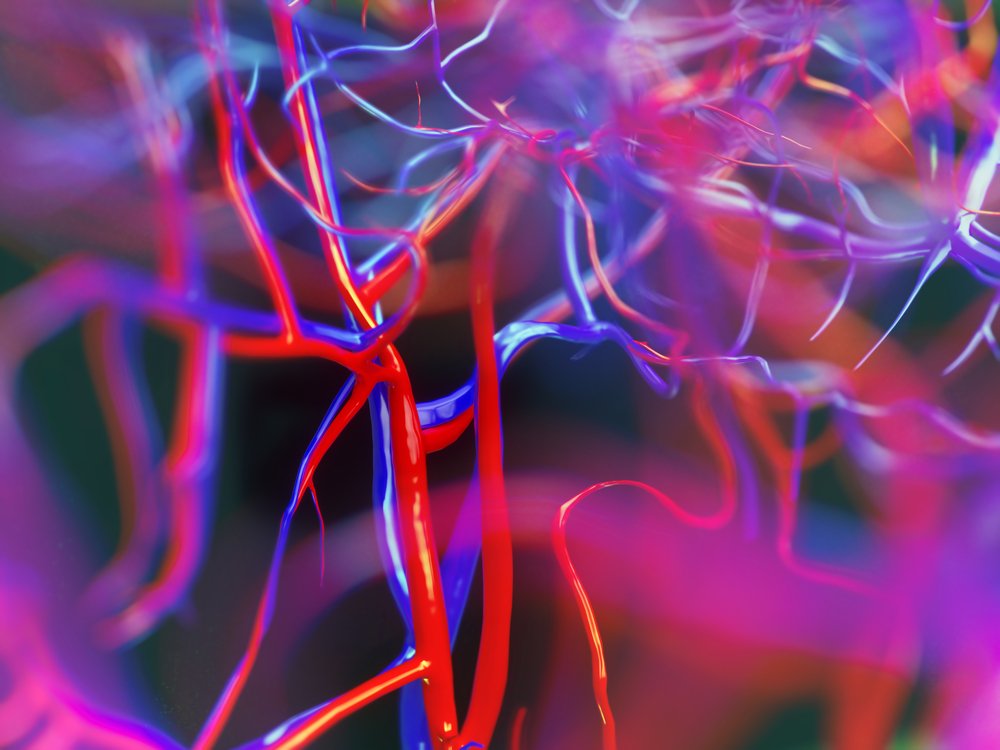

Vascular anomalies in the lung are due to changes in, as well as the loss of, microvessels. Previously, researchers have attributed this to the abnormal activity of the endothelial cells that line blood vessels, or the smooth muscle cells that surround them. Now researchers found that MPCs may be behind these changes, since they maintain blood vessels and create new ones.

Researchers found that with lung injuries such as scarring, MPCs become abnormally active and change the vascular structure of lung tissue, impairing gas exchange.

“When these cells are abnormal, animals develop vasculopathy — a loss of structure in the microvessels and subsequently the lung,” Susan Majka, the study’s senior author, said in a news release written by Leigh MacMillan at Nashville’s Vanderbilt University Medical Center. “They lose the surfaces for gas exchange.”

The team compared human and mouse MPCs collected from normal and diseased lung tissue, and found that these cells have similar characteristics and gene expression profiles. This suggests MPCs’ potential to study the mechanisms leading to PH and blood vessel anomalies.

“It’s very exciting to discover something new like this cell type that is so important in maintaining microvascular and lung tissue structure, and that has potential implications in disease and repair,” Majka said. “It’s critical to understand how different cells in the lung microenvironment regulate each other, and we really don’t know that yet.|

Indeed, understanding how MPCs work and interact with other lung cells may help further develop stem cell therapy to repair injured lungs. Majka’s team identified new targets that may potentially serve as biomarkers for the diagnosis of lung diseases. Such biomarkers may also help develop novel lung therapies.

According to Majka, by the time patients discover they have a pulmonary vascular disease, the blood vessels are already damaged. Using biomarkers to track this damage before symptoms appear would let patients begin early treatment, greatly limiting disease progression and even reversing the disease, she said.