Recognizing My Window of Opportunity for Transplantation

The changes were gradual enough not to alarm me. I went from a steady 110 to 118 pounds in less than a year, but always celebrated weight gain. The blue coloring in my lips and fingernails was more pronounced, but I figured I was just paying more attention. Determined to live as normal a life as possible, I conditioned myself to ignore the signals my body sent me.

Originally listed for a heart-lung transplant in 2002, I deactivated when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved sildenafil (OK, it’s Viagra; make all the jokes you want about my miracle drug) to treat pulmonary hypertension (PH). My pressures dramatically improved, but transplantation remained the backup plan. After another full evaluation and workup in 2015, the team told me I was sick, but not sick enough to earn necessary priority — listing me at a “Status 2” on the heart transplant list (the lungs follow the heart in a heart-lung transplant) would be “purely academic.”

Though I profess to have learned the true meaning of Christmas long ago, my heart (like that of Dr. Seuss’ Grinch) grew three sizes, compensating for failing lungs and pushing them aside in the process. My heart pounded against the constricting fabric of a dress that had fit just right months before. Instead of resenting my boyfriend who fumbled with the zipper when I needed the dress OFF NOW, I should have wondered why cushy corporate parties six months into my post-grad life were more exhausting than nights spent hiking up and down the steep hills that connect UC Berkeley’s Greek system.

Shouldering a portable oxygen concentrator and a suitcase packed with equal parts clothes, medication, and camera equipment, I boarded a plane to Seattle. Racking up business expenses for my first out-of-state photography gig, I took an Uber from the airport to a cafe. Later, I met up with a friend from college to explore Capitol Hill, eat Thai food, and crash on her couch.

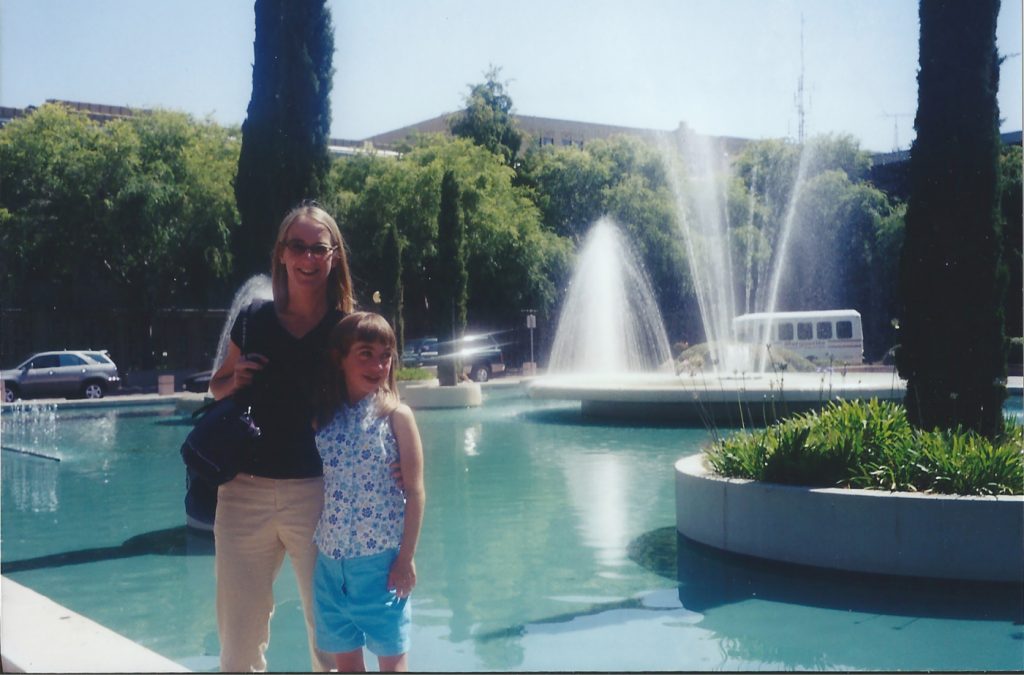

When I met Xio at orientation, I didn’t think our friendship would make it past the awkward incoming freshman stage, or that she would save my life. My classmates and I stared sleepy and green-eyed as she impressed professors by consistently interjecting insightful questions and creatively arranging sliced bell peppers. Xio and I spent most of our time together late at night under pressure, but I never imagined it would prepare us for anything other than surviving future architecture studios.

I woke up coughing, afraid to disturb Xio’s sleep. Under the light, what I had coughed into my hand was bright red, as was the mass I was now coughing up into the toilet bowl. Wheezing blood, I was busy contemplating how unfortunate it was that I was going to die in a bathroom, when I heard her voice. “9-1-1?” Xio asked. I cough-moaned agreement and listened to her calmly give directions to an operator.

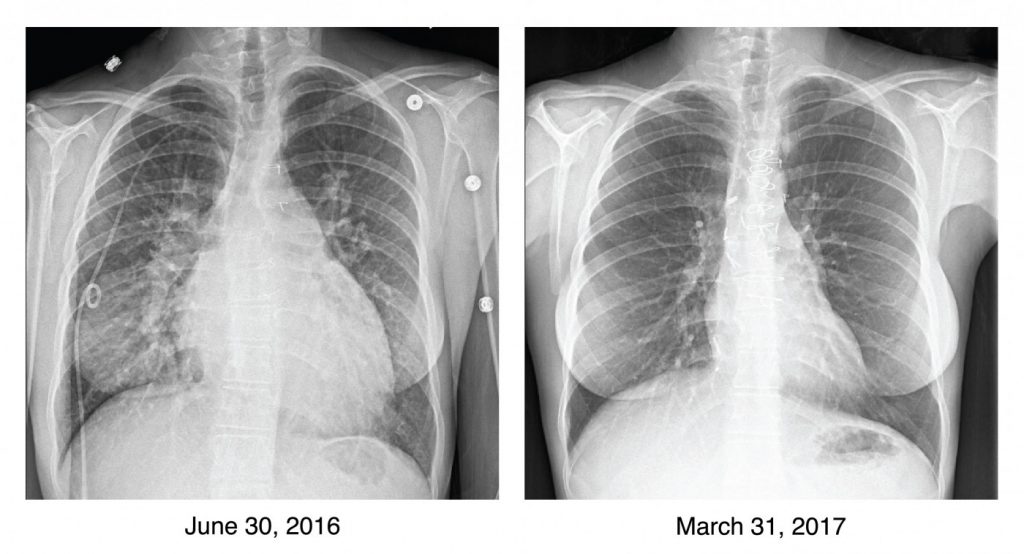

Two ambulance rides and three hospital rooms later, I learned that this event (“massive hemoptysis”) signaled a serious progression of my disease. My doctors said I was lucky to have survived it, and might not survive another event. I believed them.

My pulmonologist rejected my parents’ designs to drive me home, and instead advocated to have me medically transported by Learjet to Stanford, listed for transplant, and prioritized at Status 1B. At age 23, the decision didn’t require debate. My oxygen saturation had dropped as low as 37% and was still hovering below 90% while lying in bed on supplemental oxygen. Without new treatment options to try, I couldn’t wait another few years for improvements to transplantation. I had maxed out. After fighting PH for 16 years with transplantation locked away in savings, I wiped my account.

To say I was lucky would be an understatement. My know-it-all friend knew how to get me the help I needed, and my pulmonologist recognized my window of opportunity. Twenty-eight days after being listed, my donor and surgeons gifted me a healthy heart and lungs that not only reshaped my perspective on life, but also physically reshaped my body, making it possible for me to fit back into that dress.

***

Note: Pulmonary Hypertension News is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The opinions expressed in this column are not those of Pulmonary Hypertension News or its parent company, Bionews Services, and are intended to spark discussion about issues pertaining to pulmonary hypertension.

Leave a comment

Fill in the required fields to post. Your email address will not be published.