‘Phantom PH’ Haunts My Son Long After His Transplant

Written by |

The Mayo Clinic describes phantom pain as pain that feels like it’s coming from a body part that’s no longer there. Experts believe these sensations can be real and originate in the spinal cord and brain.

But depending on the experience, it can also be diagnosed as a psychological phenomenon. This resembles what my son Cullen has experienced following his heart and double-lung transplant. His diseased organs were replaced with healthy ones, so they aren’t the issue. It’s what Cullen came out of surgery without that still haunts him. Cullen has dealt with what we refer to as phantom pulmonary hypertension (PH).

The disease is gone, but the urgent need to supply it with supplemental oxygen and protect it with self-limitation is a psychological battle that Cullen sometimes still struggles with six years post-transplant. He has dealt with real complications, including rejection, but when he is doing well, old memories can play mind games.

Results from a recent pulmonary function test were some of Cullen’s best from the past few years. His heart is also doing well. Yet, during a snowball fight with his brother, he felt a familiar panic set in.

Cullen can do things now that he couldn’t do when he had PH. But normal exertion with exercise reminds him at times of the PH breathlessness he used to feel from simply climbing stairs or walking across a room. It can catch him off guard and cause him to think he is having trouble breathing when, really, he’s not.

It’s normal for a healthy person to feel a little short of breath after a snowball fight, but for Cullen it triggered a familiar reaction from his PH days. It made him anxious, which made his breathing more erratic.

At moments like these, he habitually asks himself, “Do I need oxygen?” He doesn’t. In fact, we haven’t had oxygen cylinders or a concentrator in our home since Cullen’s transplant.

Fortunately, episodes like these don’t happen as often as they used to. The first few weeks post-transplant were the most challenging. Cullen’s transplant team wanted him to stop supplemental oxygen and exercise his new lungs. He understood this and was compliant, but at night he struggled to sleep without it.

Sympathetic to his plight, a nurse occasionally placed an oxygen mask on Cullen, but unbeknownst to him, oxygen wasn’t running through it. Still recovering from major surgery and sedated with pain medication, it was easy to fool him with this placebo effect.

As the days passed, his mind and body became more in sync. The joy of easy breathing became the long-awaited gift he could finally fully enjoy.

After his transplant, Cullen also struggled with the loss of what he considered appendages for six years: his central line and pump that administered Flolan (epoprostenol GM). A year before transplant, another “appendage” was added that administered milrinone, a treatment for heart failure.

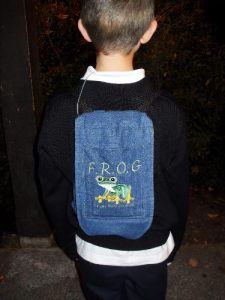

He attended grade school, bathed, and slept with these treatment pumps. Cullen often needed reminding to tuck his central line into his clothing to avoid having it accidentally pulled. The school administrator would make him smile and laugh at this annoying reminder by asking him to tuck in his tail.

Bathing was no easy task. To protect himself from infection, he used AquaGuards moisture barriers on his chest where the central line entered. Even though they sat on the floor outside of the tub, he would carefully place the pumps in zip-lock bags to protect against water damage.

To swim, he wrapped his chest in Press’n Seal, covered the pumps with multiple zip-lock bags, then squeezed himself and the medical equipment into a dry suit.

For a while post-transplant, Cullen had to protect the surgical zipper scar. When told he could allow water to gently hit his chest, I could see confusion and worry cross his face. It was not as liberating an experience as he thought it would be. He still felt the need to protect a central line and pump that were no longer there.

When getting out of bed or up from a chair, he would forget for a moment and check for his central line or reach for the backpack he carried his pumps in.

Life without the medical appendages was what Cullen looked forward to most post-transplant. He hadn’t expected to be haunted by them.

Cullen hopes that sharing these feelings with current or future transplant recipients will make them feel less crazy if they experience them, too. In time, you will enjoy more days phantom-free and breathing easily.

***

Note: Pulmonary Hypertension News is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The opinions expressed in this column are not those of Pulmonary Hypertension News or its parent company, Bionews, and are intended to spark discussion about issues pertaining to pulmonary hypertension.

Leave a comment

Fill in the required fields to post. Your email address will not be published.