Men with PAH have higher mortality, despite better measures

Researchers examine theories behind 'sex paradox' in PAH

Written by |

Despite having more favorable clinical measures, such as blood flow, men with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) have a higher mortality risk than women with the disease, according to a recent study.

This is known as the “sex paradox” and may occur because men may develop PAH only if higher risk factors are present, whereas women may be affected “more easily via causal mechanisms that are not as strongly associated with mortality,” researchers wrote.

The study, “Investigating the “sex paradox” in pulmonary arterial hypertension: Results from the Pulmonary Hypertension Association Registry (PHAR),” was published in The Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation.

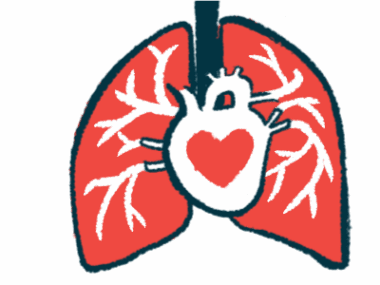

PAH is characterized by the narrowing of the pulmonary arteries, the blood vessels that transport blood through the lungs, which restricts blood flow and causes high blood pressure, or hypertension. PAH may lead to right heart failure, due to the increased workload on the heart.

Sex paradox: PAH affects more women but men have worse mortality rate

Although being a woman is one of the strongest known risk factors for PAH, men with the condition have worse survival, a phenomenon that has been referred to as the “sex paradox.”

Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain this phenomenon, particularly related to sex differences in how fast the right ventricle of the heart deteriorates, as well as dysregulated immune responses and differences in the structural alterations of pulmonary blood vessels in PAH.

To further investigate the “sex paradox” in PAH, researchers analyzed data from 1,891 adults (75% were women) included in the U.S.-based Pulmonary Hypertension Association Registry.

In women, PAH was significantly more associated with connective tissue disease — affecting the tissue that supports and holds organs together — while PAH in men was more often caused by drug/toxins or due to high blood pressure in the portal vein that runs through the liver. Men also had higher risk behaviors such as smoking and methamphetamine use.

Compared to men, women had less favorable hemodynamics (blood flow). This included higher pulmonary vascular resistance — the resistance of lung blood vessels to blood flow — and lower cardiac output, or the amount of blood the heart pumps in a minute.

Women were also more likely to be on more PAH therapies and have lower six-minute walking distances (6MWD), worse functional classsification, and worse health-related quality of life (both physical and mental).

However, sex differences were less significant when considering the body surface area, which was lower in women, or expected sex variability. Women also had a lower right ventricular stroke work index, which is a measurement of right ventricle function.

Among 1,615 patients with available follow-up data, 307 died (215 women and 92 men) over a median of nearly two years.

In PAH, women had 48% lower risk of death than men

On multivariate analysis, which includes multiple variables to find potential associations between them, women had a 48% lower risk of death than men. Further analysis revealed that age, PAH diagnosis, coexisting disorders, health-related behaviors, social determinants of health (such as income and education), 6MWD, changes in PAH therapy, and hemodynamic factors could not fully explain the difference in mortality by sex.

An alternative explanation for sex differences in mortality would be to consider whether external and unmeasured factors contribute to the sex paradox in PAH, the team noted.

“The classical example is the ‘birthweight paradox’ — among infants with low birthweight, those with mothers who smoked had a lower mortality compared to those with mothers who did not smoke. For many years it was postulated that smoking somehow reduced the risk of death in low birthweight infants,” the scientists wrote.

“In simplified terms,” the team added, “there are multiple pathways leading to development of a low birthweight infant, of which smoking is only one. The other causal pathways leading to low birthweight … are themselves strongly associated with mortality.”

“Therefore, when the population is conditioned based on disease (low birthweight) and then stratified on a risk factor for that disease (smoking), a statistical association is induced such that the risk factor (smoking) appears falsely protective. A similar effect may occur with PAH,” the researchers wrote.

Overall, this means men with PAH have a higher mortality rate than women probably because they require higher-risk factors to develop PAH and not solely because they are men. Having more high-risk behaviors could be the so-called unmeasured factor.

Other possible explanations include adverse effects of sex hormones on the heart and coexisting conditions. “Ultimately, the cause of greater mortality in men remains unclear, and may be multifactorial,” the researchers wrote.

“While sex may be an immutable factor, a better understanding of the causal structure underlying the ‘sex paradox’ in PAH provides foundations for future research and informs investigations of hormonal-based therapies for PAH,” they added.