Models show risk of hospitalization within year of PAH therapy start

Created using insurance data, models spot female sex, frailty as risk factors

Written by |

Statistical models using U.S. insurance data can help to predict the risk of hospitalization within one year of starting on treatment among people with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), scientists report.

Identified risk factors for pulmonary hypertension-related hospitalization included female sex, shortness of breath, and frailty.

These models “could be used to facilitate monitoring and timely escalation of treatment in higher-risk patients, potentially improving patients’ clinical and economic outcomes,” the researchers, who created the models, wrote.

The study, “Predicting Risk of 1-Year Hospitalization Among Patients with Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension,” was published in the journal Advances in Therapy.

‘Substantial hospitalization burden’ seen among people with PAH

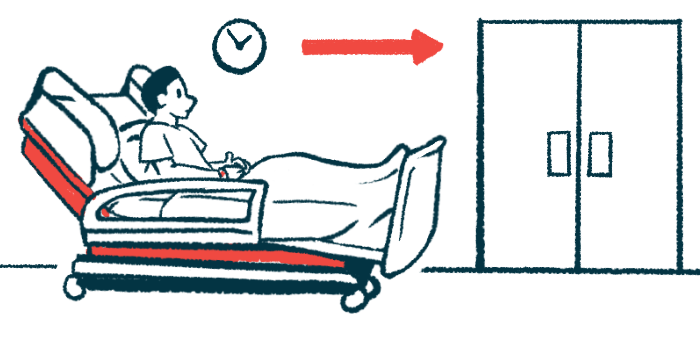

People with PAH often spend a fair amount of time in the hospital as part of managing their disease. Unexpected hospitalizations are burdensome for patients, as well as costly to the healthcare system as a whole. Better predicting when patients will require hospitalization may improve monitoring for people with PAH, ultimately allowing more timely interventions when problems do arise.

A team of scientists in the U.S. conducted statistical analyses of insurance data in an effort to identify risk factors of hospitalization for PAH patients.

Data covered 3,872 people who started on at least one PAH treatment between 2009 and 2019. Patients’ mean age was 63.1 and 60% were female. Slightly more than half of them had commercial health insurance. Co-occurring health problems like high blood pressure, congestive heart failure, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) were common.

Over the course of one year after starting on PAH therapy, a little more than one-third (38.8%) of the patients were hospitalized for any reason. About 1 in 4 (24.5%) had a hospitalization for reasons specifically related to pulmonary hypertension (PH).

“The findings of these US claims-based analyses emphasize the substantial hospitalization burden of patients with PAH and the significant need for improved monitoring and more timely interventions,” the researchers wrote.

Hospitalizations that occurred within the first month after treatment start were not counted in this analysis. According to the team, this one-month window was used to determine initial treatment patterns, such as an additional therapy being given, and to allow enough time to complete the clinical testing and administrative processes that accompany treatment decisions.

“This is important when the timing of PAH treatment initiation is likely to affect the hospitalization outcome,” the scientists noted.

Statistical models suggested that the risk of all-cause hospitalization within one year was significantly higher in patients who experienced fatigue or hemoptysis (coughing up blood). Those with worse scores on measures of frailty and co-occurring health conditions, or a history of prior PH-related hospitalizations, also were at higher risk of hospitalization for any reason.

For hospitalizations within one year deemed specifically related to PH, risk factors included female sex and dyspnea (shortness of breath), greater co-occurring health problems, a higher frailty level, and prior PH-related hospitalizations.

“The final models showed acceptable performance for predicting those patients at high risk for all-cause and PH-related hospitalization,” the scientists concluded. These models “may have utility for facilitating more expeditious care of this vulnerable patient population and may also help to avoid lengthy and costly hospitalizations.”

This study is limited by its reliance on insurance data, which is not designed for research purposes and does not include detailed clinical information, the team added.