Plant-derived substance shows promise as PH treatment: Study

FR, from coral berry plant, relaxes arteries in mice, pigs, humans

Written by |

A natural substance isolated from a houseplant shows promise as a potential treatment to prevent and reverse pulmonary hypertension (PH), a study found.

Treatment with FR900359 (FR) reversed the disease in a mouse model of PH, and relaxed pulmonary arteries of mice, pigs, and humans. FR activity was equivalent to the most aggressive triple therapy used in the clinic.

“In our experiments, FR relaxed the vessels quickly and effectively and produced a good therapeutic effect,” Alexander Seidinger, research assistant in the department of systems physiology at Ruhr University Bochum and the study’s first author, said in a university news story.

The study, “Pharmacological Gq inhibition induces strong pulmonary vasorelaxation and reverses pulmonary hypertension,” was published in EMBO Molecular Medicine.

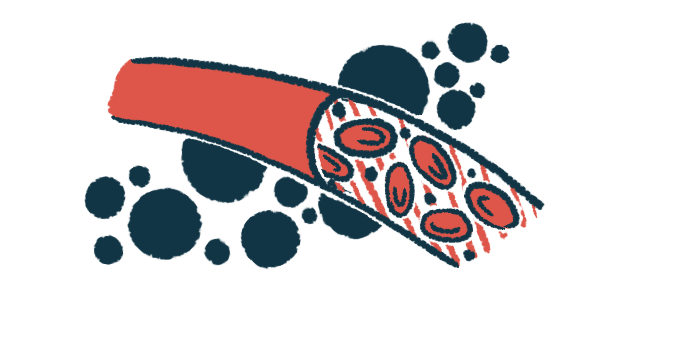

PAH is characterized by the narrowing of the pulmonary arteries, restricting blood flow and raising blood pressure. This narrowing is the result of the uncontrolled growth of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells (PASMCs), which contribute to the progressive thickening of pulmonary artery walls. As a result, the heart’s right ventricle needs to work harder to pump blood, increasing the risk of heart failure.

Messengers target multiple receptors, current therapies don’t

While the signaling messages that promote blood vessel tightening act via multiple protein receptors at the cell surface, each current therapy targets a single receptor.

“There are many of these so-called vasoconstrictors,” Seidinger said. “And each one has its own receptor. A single blockade is therefore not very effective.”

Past research has shown that Gq proteins, which bind to G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), are implicated in PAH. GPCRs “are the largest family of drug targets,” the researchers wrote, adding that about one-third of all approved drugs target them.

“Within the cells, there are only a few pathways through which the signal for vasoconstriction is passed on,” Seidinger said. “So-called Gq proteins are involved in many of these pathways. This makes them a good target for intervention.”

FR, derived from Ardisia crenata, also known as coral berry, has been shown in past studies to selectively inhibit Gq proteins. With this in mind, the researchers assessed the effects of FR in counteracting pulmonary blood vessel tightening and growth of PASMCs in PAH.

Results using isolated pulmonary vessels from mice showed FR-mediated strong relaxation after previous tightening with molecules that signal through Gq.

The researchers observed the same thing when they used pulmonary arteries isolated from pigs, whose blood vessels more closely resemble those of humans, and human lung samples.

The most aggressive triple therapy regimen for PAH combines medicines working in different ways. An endothelin-1 antagonist, a phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor, and a prostacyclin analog all work to relax blood vessels. The scientists compared the effects of FR to those of a combination of Tracleer (bosentan), generics also available; Revatio (sildenafil); and Ventavis (iloprost).

In mouse pulmonary vessels, the relaxing effect of FR alone was much stronger than that of any of the therapies alone. Moreover, a single dose of FR exerted similar relaxation to the triple-combination therapy. When added on top of the combination therapy, FR even enhanced blood vessel relaxation.

In a mouse model of PH, FR was able to relax blood vessels in lungs by 90% within eight minutes, which supports “the strong vasorelaxing effect of FR even under PH conditions,” the researchers wrote.

FR also prevented the thickening of pulmonary vessel walls in a different, standard PAH mouse model. The increased pressure in the heart’s right ventricle could be almost completely prevented by repetitive FR application.

“The thickness of the muscle layer around the pulmonary vessels decreased – or didn’t even increase in the first place,” Seidinger said.

As effective therapies are needed for established PH, the researchers next tested whether treatment with FR was able to reverse the disease in mice. Administration of FR three weeks after PH development lowered blood pressure in the right ventricle and reduced blood vessel thickness. Infiltration of immune cells called macrophages in the lungs, which indicates inflammation, also was reduced.

The findings support FR as “a promising drug candidate for the treatment of the disease,” Seidinger said. “However, it will certainly take many years of intensive research before it can be used in clinical practice,” he added.