PH Mortality Rates Increased 2% Annually in US for Past 20 Years

Higher risk of death found for women and Black and older people

Despite treatment advances in pulmonary hypertension (PH) over the last two decades, the age-adjusted PH-related death rate in the U.S. increased annually between 1999 and 2019, with mortality climbing by nearly 2% each year, a new study found.

The simultaneous presence of PH and disease of the left side of the heart appeared to be a significant contributor to this increased mortality rate over time, according to researchers.

Also, women, non-Hispanic Black people, and older people were those at higher risk of pulmonary hypertension-related death.

These study results highlight the need for better therapeutic approaches for PH and improved care approaches for patient populations at a higher risk, the team noted.

“We believe that the current findings indicate a call to action,” the researchers wrote. “[Pulmonary hypertension] due to both chronic lung disease and left heart disease deserve ongoing focus as the total number of deaths with PH in these conditions remain very high and reflect a major public health problem.”

The study, “Pulmonary Hypertension Mortality Trends in United States 1999-2019,” was published in the Annals of Epidemiology.

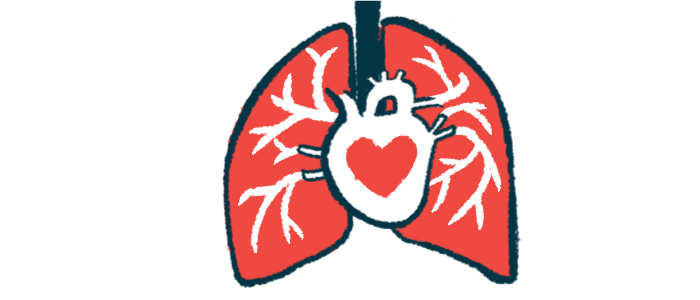

PH is characterized by high pressure in the blood vessels supplying blood from the heart to the lungs. This can force the right side of the heart to work harder to pump blood, making it progressively weaker and eventually leading to heart failure.

While all types of pulmonary hypertension are associated with increased mortality, some reports suggest higher death rates for those caused by left-heart disease, and common lung conditions.

Previous studies had shown that the age-adjusted PH-related mortality rate in the U.S. remained stable from 1980 to 2001, but then gradually increased until 2010 — from 5.2 to 6.5 deaths per 100,000 individuals.

Data also revealed that non-Hispanic Black people were at a significantly higher risk of death than non-Hispanic white people (9.1 vs. 6.5 deaths per 100,000 people in 2010).

Investigating recent trends

Now, a team of researchers at Emory University School of Medicine, in Atlanta, set out to evaluate more recent trends in PH-related mortality in the U.S. The researchers also investigated age, sex, and race disparities.

PH-related mortality rates were evaluated among people ages 15 and older, from 1999 to 2019. Data were collected from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiology Research database, known as WONDER.

WONDER compiles data from all death certificates in the U.S., and includes single and multiple causes of death, and demographic data such as age, race, and sex.

The team extracted the age-adjusted mortality rates by 10-year age groups, race/ethnicity, sex, and simultaneous health conditions, called comorbidities. They selected both PH and comorbidities that may be associated with PH: left-heart disease, lung disease, liver disease, obesity, diabetes, and connective tissue disease.

Results showed that, over the 20-year span, 429,105 deaths included PH as one of the multiple causes, corresponding to an age-adjusted rate of 7.9 deaths per 100,000 people. During this period, the rate of PH-related deaths significantly increased by 1.9%, on average, per year.

A significant increase in the PH-related mortality rate was observed in both women and men, but females showed both higher rates (8.3 vs. 7.4 per 100,000 individuals) and greater increases over time (2.3% vs. 1.1%).

While pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is known to affect more females than males, this type of PH is relatively rare. As such, these sex-related differences suggest that “other forms of PH may also be more common — or more commonly recognized — among women at the time of death,” the researchers wrote.

“Additional work is needed to understand gender differences in other forms of PH,” they added.

PH-related mortality rate also increased with age, from less than one death per 1,000 people ages 15–24 years to more than 100 deaths per 1,000 people 85 years or older.

Increased mortality for women, Black people

Over the study period, there was a trend for mortality rates to drop or remain stable in younger age groups (those 15–54 years), and to increase in older groups. Also, mortality rates increased at a higher pace for people ages 75 and older.

“While this could be a phenomenon of the aging U.S. population, or increased recognition of PH, it likely reflects that PH is a late complication of the accumulation of chronic cardiopulmonary conditions and is common among those 65 and older,” the team wrote.

The researchers also found that age-adjusted pulmonary hypertension-related death rates varied significantly by race/ethnicity.

The rate was lowest for non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander people and Hispanic people (fewer than five deaths per 1,000 people) and highest for non-Hispanic Black individuals (11 deaths per 1,000). Non-Hispanic white people showed a mortality rate of 7.1 deaths per 1,000 people.

The highest age-adjusted mortality rate of any sex and race group was among non-Hispanic Black females, with 12.2 deaths per 1,000 people.

“Increased prevalence of heart failure, [high blood pressure], and diabetes among Black persons, all of which promote PH, may explain the observed higher mortality rate in our study”, the researchers wrote.

“Alternatively, a separate study of racial disparities in PH mortality found that socioeconomic status fully explained the observed differences, suggesting that social determinants of health may [underlie] our observations,” they added.

Regardless of these race differences, mortality rates from 1999 to 2019 increased for all race/ethnicity groups, ranging from 2% to 2.8% increase per year.

Moreover, age-adjusted mortality during the study period was similar between people with PH and left heart disease — the most common cause of PH — and those with PH and chronic lung diseases: 3.8 vs. 3.1 per 1,000 people. Chronic lung disease is the second most common cause of PH.

Notably, mortality rates increased significantly by 3.9% each year for those with PH and left-heart disease, while they remained unchanged for those with PH and chronic lung conditions.

People with PH combined with obesity, diabetes, liver disease, or connective tissue also showed an increase in mortality rates, by 2%–4.3%.

These findings highlight an “increasing frequency of deaths associated with PH over the last 20 years (1999–2019)” in the U.S., the researchers wrote

“Deaths with PH are experienced more in women, [non-Hispanic] Black persons, and older populations,” the team wrote, adding that “these differences are worsening over time, including over the 2010–2019 period which has not been previously reported.”

The researchers concluded: “There is a need to prioritize research … focused on common causes of PH.”