Surge in Telemedicine One ‘Good’ Outcome from COVID-19 Crisis, Doctors Say

Written by |

While there are few silver linings to the cloud created by COVID-19, the pandemic that has killed tens of thousands, hobbled economies worldwide and drove millions to quarantine in their homes, one may be a new appreciation of telemedicine.

“If something good could come out of this crisis, it’s that we would learn how valuable telehealth could be to our community,” said Steven Shook, a neurologist at the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio. Shook specializes in neuromuscular disorders such as Parkinson’s, muscular dystrophy, myasthenia gravis, spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), and amyloid lateral sclerosis (ALS), and in polyneuropathy.

“People are going to want more — they’re going to want it to continue to be part of their medical care,” Shook said in a phone interview with Bionews Services, the parent company of this website.

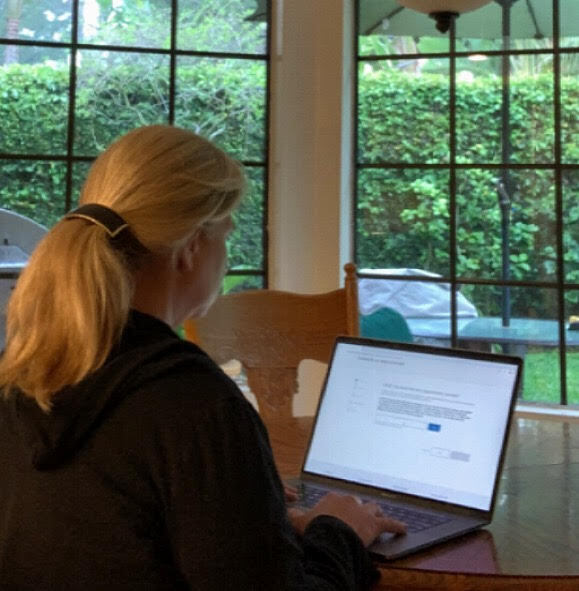

Telemedicine is the use of technology, devices like a laptop or desktop, telephone or smartphone, to connect directly with a healthcare professional — doctors, specialists, nurses, therapists, psychologists — from just about anywhere you can get a connection: your home, your car, your office.

It’s the doctor’s house call, 21st century style.

But it arguably took a pandemic to bring telemedicine to the fore.

COVID-19 is a highly contagious and utterly new coronavirus, and its arrival put doctors’ offices and hospital visits off-limits to all but emergency cases.

People who have chronic diseases or take treatments that weaken or suppress their immune systems — whether Crohn’s, Friedreich’s ataxia, lupus, lymphoma (and most cancers), multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, or scleroderma — are at special risk of infection. So are those with disorders of the airways, such as cystic fibrosis, pulmonary fibrosis, and COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease).

“I will continue to use telemedicine as I did before: as a tool for when it is harmful for me to go in or I am unable to physically go in to see my physician,” said Jennifer Powell, a 51-year-old Californian with secondary progressive multiple sclerosis (SPMS). But “I still think it is very important to be seen in person.”

As access closed in recent weeks, healthcare professionals, policymakers, and patients started taking a fresh look at the potential of telemedicine — video encounters, phone conversations, and e-visits (email-like exchanges) — to meet everyday health needs, from routine checkups or procedural follow-ups, to prescribing or refilling medications.

Shook’s use of telemedicine rocketed from “about 5% of my personal practice” as of late February, to “on March 16, a Monday, 100%. Excluding procedures I do, 100% of my new, involved visits are virtual.”

Jeff Gelblum, a board-certified neurologist and psychiatrist with First Choice Neurology near Miami, Florida, saw a similar, “fundamental pivot” in his work.

“Historically, I would do one televisit a day, mostly for people who were busy or working or out of town,” Gelblum said. “Now I’m doing 20 televisits a day for people self-quarantining at home.”

A crucial policy shift, at a critical time

If a virus was the impetus, two changes to U.S. government rules concerning telemedicine — how it might be used, where its use could be reimbursed — were the linchpin.

The federal Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services opened access to telemedicine and a provider’s right to be paid for such services to all Medicare users, at rates equivalent to an in-person office visit, in a March 17 announcement.

Before this order, retroactive to March 6, reimbursement was largely restricted to televisits with people in “designated” rural areas.

At the same time, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services waived HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) enforcement and penalties concerning the type of systems that could transmit or store personal medical data. This allowed “providers that serve patients in good faith” to use “everyday communications technologies, such as Apple FaceTime or Skype.”

Both revisions stand “on a temporary and emergency basis,” meaning they might be in place only for the duration of the current crisis.

Reimbursement probably was “the most important” change, said Rakhee Langer, vice president for healow, a telemedicine platform offered by eClinical Works, a healthcare technology company based in Westborough, Massachusetts.

Demand on healow, a secure, HIPAA-compliant, and multi-feature app used by more than 40,000 physicians across the U.S., went from an average of 100,000 daily usage minutes in January through early March, to 1.5 million minutes daily starting at mid-month, Langer said.

“I think there’s going to be continued adoption,” she said. “The patients and doctors have crossed the technology hurdle.”

Similar shifts are being reported across Europe, with countries that include France, Germany, and the U.K. moving to ease their own reimbursement and privacy restrictions. But the European Union’s regulatory environment and mix of state-run health systems has, until the pandemic, been less welcoming of telemedicine than in the U.S.

“What I would love to see is the government to take a good, hard look at the value we deliver during this period of time, and to consider not rolling back those changes,” Shook said.

Telemedicine at its best: ease and convenience

Ease of use, for both healthcare providers and patients, is one of the most important features of telemedicine.

Shook remembers being outfitted with “a special camera, a special microphone” when this service first came into use at the Cleveland Clinic in 2014. Today, he finds he’s “gotten very comfortable with using my cellphone.”

Convenience, the ability to connect to a doctor without leaving where you are, arriving at an office and waiting in a chair, is another.

Telemedicine “keeps me from having to drive — sometimes over an hour away — to a specialist, so it is saving in travel and expenses,” said Brittany Foster, 28, of Rhode Island, who was diagnosed with pulmonary hypertension due to congenital heart disease shortly after her birth, and with Currarino syndrome, a rare genetic disease typically affecting the lower spine (sacrum), rectum, or presacral soft tissues, at age 3.

“The doctors are usually on time, from my experience, when it comes to telemed,” she said. “There’s no need to wait around in an office … which saves my own anxious thoughts.”

But it’s not just 20-, 30-, or 40-year-olds who might appreciate the technology and what it can offer. Older people may stand to benefit the most.

Younger patients, including millennials “who obviously have mobile devices, some literally attached to their bodies,” were the first to adopt telemedicine, Shook said. “But I’m noticing that my patients who are older … people who never even thought of doing this before, are really impressed by how easy it is to do.”

My “ALS patients are a great example of how we can connect … and provide excellent care virtually,” he added. “It’s very hard for them to get back and forth between their home and the clinic.”

“Historically, Medicare refused to avail patients of telehealth. Why? I don’t know,” said Gelblum, whose patients include those with Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s. “Because Medicare beneficiaries being older and more infirm would have the greatest difficulty physically going to the doctor.”

The Cleveland Clinic’s platforms are AmericanWell (amwell) and Express Care Online, which — like healow, which Gelblum uses at First Choice — are well-integrated into their respective centers’ electronic health (or medical) records (EHR/EMR) system.

All three platforms are secure, compliant, and largely walk people through initial steps of any medical visit: sending out appointment notices or reminders that include links, and filling out a health questionnaire for a doctor to review before inviting the patient “into the office.”

They allow a provider to pull up charts, lab results, imaging scans, and other records; an invite is sent once everything’s ready. Both also support wearable apps that can monitor issues such as gait or tremor, and — if a patient has the necessary tools — can instantly display blood pressure, blood-oxygen levels (pulse oximeter), or heart rate measures.

“In my patient population, a lot are visually challenged, memory challenged, dexterity challenged,” said Gelblum, whose oldest televisit patient is 102. “Simplicity is crucial.”

Security is also crucial, and Gelblum disagreed with the government’s opening of telemedicine to popular platforms, like FaceTime or Skype, created for social media.

“You’re allowed to drink a whole bottle of Scotch, but that doesn’t necessarily make it a health choice,” he said. “I think it’s important to remember that, even though … these platforms exist, they don’t always exist for the benefit of the user, or for the benefit of a patient.”

But the need to ramp up a large country, with an estimated 100 million people with chronic conditions, and shift it virtually overnight from face-to-face visits to video or telephone care likely left little choice.

Shook said the Cleveland Clinic’s systems were overwhelmed with demand in mid-March, and its technology department settled on adding FaceTime and Google Duo for their popularity, and “as the most secure from an ITD [information technology department] standpoint.”

He expects that his academic institute’s goal is to return fully to its secure and traditionally HIPAA-compliant platforms.

Looking ahead

People with chronic diseases whom we talked to, all who also work with Bionews, favor the convenience of telemedicine as an alternative form of essential care.

“I think that it is great to have telemed as an option. Particularly for the days when I am not feeling my best,” Foster said. On “a follow-up appointment, for example, it seems like I am simply updating the doctor on my status when that can be said over a phone call or check-in email.”

Still, she mentioned being able to better hide possibly serious health concerns when using the medium. “Over the phone,” she said, “I can paint a picture that everything is ‘great’ due to wanting to avoid a hospital admission or wanting to avoid care out of fear.”

Televisits conducted by caregivers who know her well, however, usually don’t allow skipping pointed discussions. And her “doctors usually ask about vital signs,” she added, even though “self-monitoring equipment isn’t something that was ever offered.”

Powell worried that doctors and patients alike would favor the “convenience of a diagnosis or prescription without leaving your home,” and forego “a thorough examination.”

Her own doctors have been vigilant in not allowing her to sidestep essential visits, she said. “However, it’s a slippery slope that is only as good as the institution implementing the telemedicine.”

But the “good outweighs the bad,” she added, especially for those “with weakened immune systems or … trouble with mobility.”

Shook and Gelblum agreed, emphasizing that, once a relationship is established with a patient, many routine exams — across diseases — can be conducted online.

“I don’t think we’re going to ever completely replace that human-to-human interaction that’s so critical in medicine,” Shook said, “but I do think that some of the work we do can be done very effectively on a virtual platform.”

Telemedicine’s “greatest advantage,” said Gelblum, “is that it promotes accessibility in medical care. … Accessibility to care is an enormous hurdle, and that is probably the greatest reason why people get sick.”