Pulmonary Hypertension: One Family’s Long, Hard Journey

Written by |

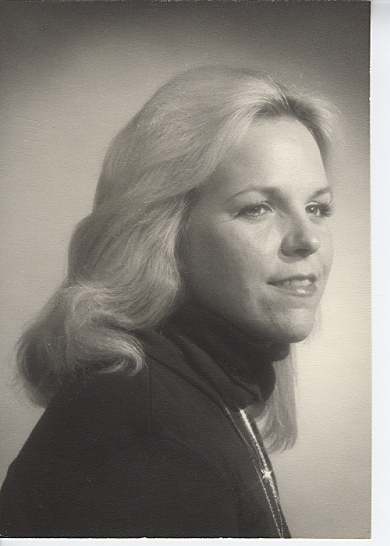

Erica Huntzinger, today a pulmonary hypertension (PH) activist and advocate, remembers her mother, Susan, beginning to experience PH symptoms in her mid-30s, but going improperly undiagnosed for more than a quarter century. During this period, Susan suffered two respiratory failures, a heart attack, and as many as five emergency room visits a year for shortness of breath. During those years of struggle with chronic illness, “not one doctor, nurse or respiratory therapist ever mentioned PH,” Erica said in an exclusive interview with Pulmonary Hypertension News. “Looking back, all the signs were there, but it was many years until someone connected the dots.”

Part of the reason PH has historically been a neglected disease relative to, say, cancer, heart disease, or diabetes, is doubtless due to PH onset often being vague and insidious. Its early symptoms, like shortness of breath and fatigue, are shared with, and more commonly attributable, to other diseases and conditions. In fact, PH is often misdiagnosed as asthma.

But even after PH, defined by the Pulmonary Hypertension Association (PHA) as “high blood pressure in the lungs,” progresses to a more distinct and aggressive symptom profile (including dizziness, chest pain, heart palpitations, lower extremity swelling or edema, and prominent neck — jugular— veins), the disease often remains under the radar diagnostically. According to The Asthma Center, patients with PH may also show evidence of decreased oxygen levels during exertion, rarely seen in non-acute asthmatic individuals, but PH diagnosis may also be complicated by the potential for both asthma and PH to co-exist in a patient.

Today, the American College of Cardiology has a set of Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension, and also a screening guidelines resource. Awareness of the disease is increasing, but Erica said there’s still plenty of room for improvement: “I hope in time there will be a screening recommendation or guideline for a more broad patient population.”

Today, the American College of Cardiology has a set of Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension, and also a screening guidelines resource. Awareness of the disease is increasing, but Erica said there’s still plenty of room for improvement: “I hope in time there will be a screening recommendation or guideline for a more broad patient population.”

Interested in PH research? Check out our forums and join the conversation!

By the time Susan finally received an accurate diagnosis in 2005, she was in what is now considered stage 3 or stage 4 pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), a specific variant of PH in which the disease process occurs in the pulmonary arteries themselves, causing arterial walls in the lungs to tighten and stiffen. Doctors told her she was too ill to withstand the heart and/or lung transplant surgery that helps some PH and PAH patients, and that she had only a few years to live.

“It was hard for us to believe that my mom had been misdiagnosed for most of her life, and that medically there was so little to offer her,” Erica said. “It was very frustrating for all of us to come to terms with the diagnosis of PH. But my mom was determined to live as fully as possible, and my dad and I supported her as best we could in doing that. We shifted priorities and started to think about how to enjoy life more, and create opportunities for my mom to get together with her friends, or go out and do something fun, rather than just focusing on the medical things.”

“My mom started to use a power chair and that led to my parents making some changes around their household to make things easier for her to manage,” Erica added. “In terms of moral and emotional support, my mom created her own support system of family and close friends, including people in her faith community. She also saw a therapist. My parents also had three dogs who were protective and loving companions for my mom.”

Susan died in 2009.

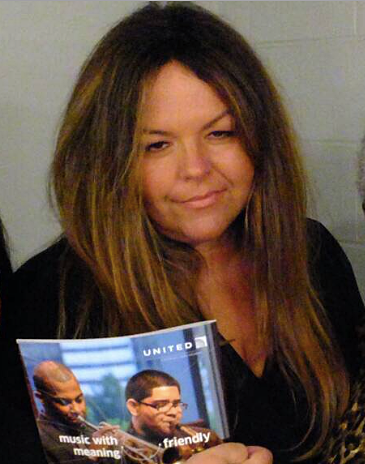

In 2013, when Erica’s aunt and Susan’s older sister, Barbara, described various health challenges she was dealing with, it seemed likely to Erica, who had accompanied her mom to countless doctor appointments and dozens of ER visits and hospitalizations over the years, that Barbara had started on a similar disease path.

Erica, who has a master’s degree in Public Health from the University of California, Los Angeles, and a professional background in healthcare, suggested that Barbara ask her doctors to arrange testing and screening for PH. The doctors agreed, and results confirmed a definitive — and in this instance more timely — diagnosis of PAH, at stage 2 rather than stage 3 or 4. The good news, Erica said, is that today PAH is better understood than when her mom was diagnosed in 2005, with approved medications that were not available to Susan. Barbara has been able to make changes and adjustments that help her to go on living her life as fully as possible, and “is managing well on her treatment plan” Erica reported. “She has not had an ER visit or hospitalization since her diagnosis almost two years ago.”

However, the question remains: how long might Barbara have gone undiagnosed had Erica not recognized an all too-familiar pattern?

After Susan died, Erica and her dad, John, now also deceased, vowed to work to share what they had learned with other PH/PAH patients and their families. “My mom wanted others to be helped through her experience, so after she passed away my dad and I reached out to the [Pulmonary Hypertension Association] to see how we could get involved. We participated in legislative advocacy campaigns and a market research study. That study played a big part in the launch of the early diagnosis campaign called ‘Sometimes It’s PH,’” an initiative to reduce the interval between onset of symptoms and a PH diagnosis.

PHA notes that a delayed or missed diagnosis is still the biggest barrier to care for PH and PAH patients, with almost three-quarters of these patients today having advanced PH by the time they are diagnosed.

“After that, PHA asked me to help launch the first PSA [public service announcement] campaign on television,” Erica said. “I also worked on the second PSA campaign, #Heart2CurePH, launching it on television in the top 10 markets all over the country.”

Although relatively rare, with an estimated prevalence of 15-50 cases per million, PAH incidence in certain at-risk groups is substantially higher. For example, it strikes women twice as frequently as men, with an average age of 36 at diagnosis. The American Thoracic Society (ATS) says that while the exact prevalence of all types of PH in the United States and elsewhere is unknown, the number of U.S. patients is “certainly in the hundreds of thousands, with many more who are undiagnosed.” ATS estimates that about 200,000 hospitalizations occur annually with PH as a primary or secondary diagnosis, and “roughly 15,000 deaths per year are ascribed to pulmonary hypertension, although this is certainly a low estimate.” The ATS also cites study data indicating that with improved treatments and survival, the number of U.S. patients living with the disease has increased to between 10,000 and 20,000.

According to the Pulmonary Hypertension Association, PAH patients who have one or more blood relatives also afflicted with the disease are said to have familial PAH (FPAH), also known as heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension (HPAH). Of the several hundred U.S. familiesbelieved to have FPAH, the disease in most of them is caused by an inherited mutation in a gene encoding a protein called bone morphogenetic protein receptor 2 (BMPR2), which helps regulate the growth of cells in the walls of the small arteries of the lungs.

The PHA suggests that other factors, probably genetic or environmental, are also needed for disease development, because only about 20 percent of individuals with the BMPR2 mutation ever develop FPAH, which can occur at any age and affects women almost three times more frequently than men. The National Institute of Health’s Genetics Home Reference notes that mutations in several other genes have also been found to cause PAH, but are much less common causes of the disorder than BMPR2 mutations.

Asked if either Susan, Barbara, or herself had been tested for the BMPR2 gene, Erica said: “No health provider ever asked my mom or my aunt to do any genetic testing. I don’t know how much was known about it before 2009, at a time when my mom might have been willing to be tested. I have no symptoms of PH and have not been tested.”

Such testing is also not a priority for her.

“I feel the focus really should be on early diagnosis, and increased awareness and improved education about PH in the delivery of healthcare,” she said, “including those who work in emergency rooms. … Many times patients who are in distress with their breathing will go to an emergency room, so I feel there is a great opportunity there to make a difference for PH patients, and help end the cycle of misdiagnosis.”

As to what suggestions she might offer people thinking they may have PH, Erica said: “I think if a patient might suspect they had PH, the best thing they could do is talk to their doctor about it. But I don’t know how many patients might experience the cardinal symptoms and ask themselves, ‘Do I have PH?’

“What happens sometimes is a patient may have asthma or COPD [chronic obstructive pulmonary disease], and perhaps they are not improving with treatment. Then, they should continue to talk to their physician. Some articles have been written in recent years about asthma patients’ readmissions to ER’s, and these patients are probably being asked to be compliant with their meds, or their meds are being increased,” she said. “I wonder if anyone has considered that maybe they don’t have asthma, maybe they have another condition? The general assumption for shortness of breath symptoms is asthma, but maybe that has to be thought about a little differently.”

Erica refers to a video in which Dr. Robert P. Frantz, a cardiologist and director of the Mayo Clinic’s Pulmonary Hypertension Clinic in Rochester Minnesota, discusses the challenges associated with diagnosing PH as being something doctors have to think about, and “an awareness issue.”

Erica refers to a video in which Dr. Robert P. Frantz, a cardiologist and director of the Mayo Clinic’s Pulmonary Hypertension Clinic in Rochester Minnesota, discusses the challenges associated with diagnosing PH as being something doctors have to think about, and “an awareness issue.”

“I wish there was something like the handheld device in the Star Trek movies that could scan a patient,” Erica concluded, “some type of scanner or sensor that could tell us what is going on. I hope someday there will be something like that. I hope in the future there will be some type of standard recommendations as to when to screen a patient for PH. This is something for the medical experts to decide.”

Sources:

Erica Huntzinger

The Pulmonary Hypertension Association (PHA)

The American Thoracic Society

The Asthma Center

Mayo Clinic

American College of Cardiology

National Institute of Health Genetics Home Reference