In Defense of Transplant, Part II: Measuring Survival Rates

Written by |

Second in a series. Read part one.

I’ll be the first to admit that I did not want a transplant. Even when I was dying, I didn’t want a transplant. I was scared. But I was dying, and I was 23 years old. So, I said yes.

As I said last week, I’m not a fan of survival statistics (or statistics in general). Lately, I’ve been encountering so much — well, negative publicity, if you will — about transplants that I started researching what those “abysmal” survival statistics actually look like. So, here we go.

In a 2017 report from the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT), adults who underwent primary lung transplantation between January 1990 and June 2015 had a median survival of six years. Median survival rates continue to improve, with conditional median survival for lung transplant recipients transplanted between 1999 and 2008 at eight and a half years. That means that half the patients who survive the critical first-year post-transplant are still alive eight and a half years after their operation.

Anecdotally, I know several recipients between 10 and 20 years post-transplant. Reason number one I don’t care for statistics.

That’s just patients I’ve met in person. Harefield Hospital patient (and Guinness World Record holder), Andrew Whitby, lived over 32 years after his heart-lung transplant. The first successful heart-lung transplant (first with long-term survival) was performed 37 years ago at Stanford Medical Center in 1981. The first successful isolated lung transplant was performed just 35 years ago. These are relatively new procedures with no established caps on survival.

We don’t have the same extensive data collection system for PH patients that we do for lung transplant recipients, so survival statistics are difficult to predict. That 25-year dataset I quoted above included 53,396 transplant recipients. The first study of mortality in “primary pulmonary hypertension patients” (now referred to as pulmonary arterial hypertension patients) published in 1991 included only 194 patients. A study published in 2015 through the same registry (that grew to include 55 institutions) considered 2,039 previously diagnosed and 710 newly-diagnosed patients — 2,749 patients. This is the trouble with rare diseases. Reason number two I don’t care for statistics.

Anyway, back to that first study of mortality in PAH patients. This was a study of patients diagnosed in the 1980s when treatments for pulmonary hypertension did not exist (Flolan received United States FDA approval for treatment of PAH in 1995). The median survival of these patients was 2.8 years. Aha! This is why the cardiologist who diagnosed me in 2000 told my parents I had about three years to live. Reason number three I don’t care for statistics.

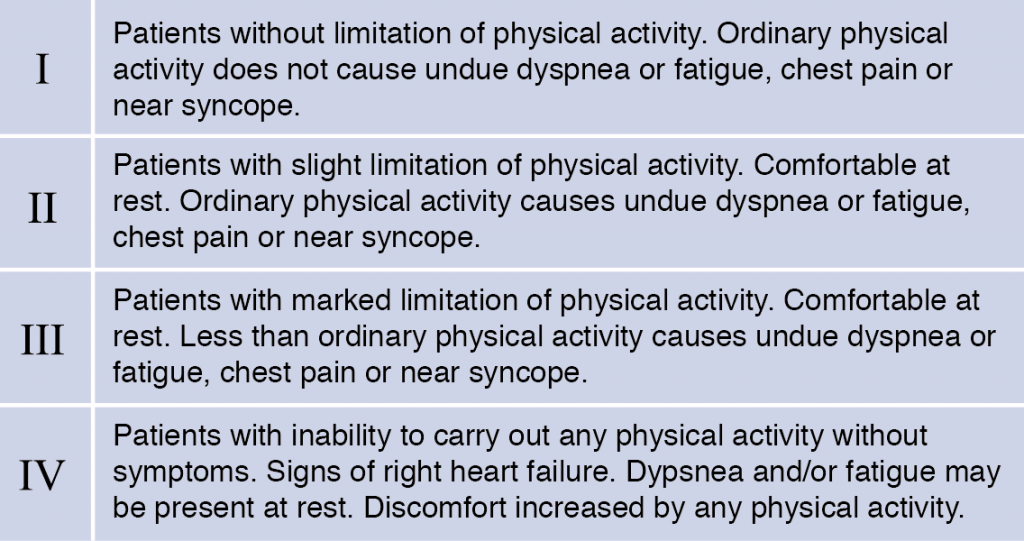

Back when that study was done, all 194 patients were lumped together because we didn’t have WHO classification. Who? This isn’t a knock-knock joke — stay with me. The World Health Organization (WHO) divides PH patients by functional class. Refer to the table below for the definitions of each of the four classifications.

This table is an edited version of WHO functional assessment for pulmonary hypertension from the Cleveland Clinic website.

A retrospective study published in 2014, after the development of WHO functional classification (WHO-FC), estimates that the median survival for (untreated, 1980s) patients in classes I and II were six years. Much better! But for WHO-FC IV patients, it was six months. Now that’s abysmal! Clearly classification matters in our heterogeneous patient population.

Yeah, but that was without treatment and in the 1980s. You’re right, survival statistics have improved quite a bit with more research and therapies available. Looking at the study of 2,749 patients I mentioned earlier, patients newly diagnosed at time of enrollment in the study (between 2006 and 2009) had estimated five-year survival rates of 72.2, 71.7, 60.0, and 43.8 percent for WHO-FC I, II, III, and IV, respectively. The poorest outcome was among patients diagnosed before enrollment in class IV who had a five-year survival rate of 27.2 percent.

Though not viable for all patients, a heart-lung transplant or double-lung transplant is the only treatment for end-stage pulmonary hypertension. In end-stage pulmonary hypertension, patients have exhausted all therapeutic options and show signs of heart failure (edema, irregular heartbeat, fatigue, and so on). Sounds a lot like those WHO-FC IV patients who were receiving treatment and still had a 27.2 percent five-year survival rate, yes?

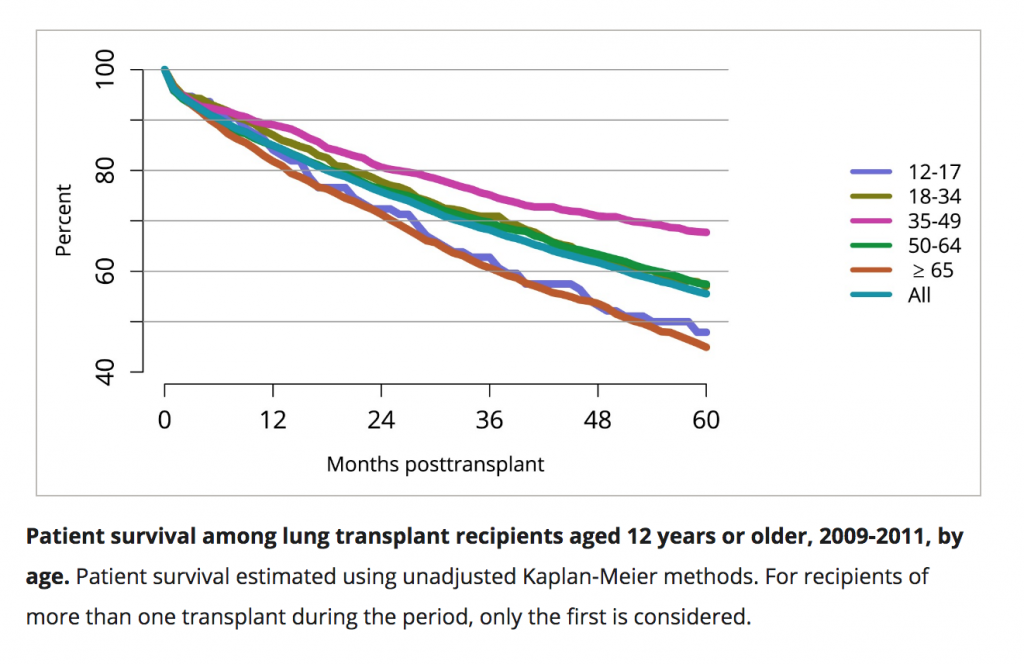

Using the Kaplan-Meier estimator, the OPTN and SRTR 2016 Annual Data Report predicted five-year survival rates of 55 percent for all lung transplant recipients and nearly 70 percent survival rate for recipients between the ages of 35 and 49. Refer to the graph below.

Hold up. You mean to tell me the survival rates that keep me up at night include patients who received their transplants when they were 65 years old and older? Don’t get me wrong; I’m thrilled that nearly half of those patients are living into their 70s. But that’s going to skew some of the numbers, friends. Reason number four I don’t care for statistics.

Even if we include the 12-year-olds who maybe don’t always take their medications, and other outliers, a 55 percent survival rate sounds better than 27 percent. And that comes with all the quality of life and functional capacity stuff? Sign me up!

Ha. We’ll save that for next week.

***

Note: Pulmonary Hypertension News is strictly a news and information website about the disease. It does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. This content is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The opinions expressed in this column are not those of Pulmonary Hypertension News or its parent company, Bionews Services, and are intended to spark discussion about issues pertaining to pulmonary hypertension.

Kaye Norlin

I know people 27 and 28 years post lung transplant, not from PH. Since I was 66 at time of transplant, I plan on being one of those people who makes it a long time. I did go into this with the knowledge that I had a 70% chance of making it through the first year and maybe would make it 5 years. Statistics are interesting but can be used or interpreted in ways to suit your needs. So I look at them (I am a science geek) but I am determined to help raise that line for people over 65 at transplant.